I’m delighted to see that David Bowles of The McAllen Monitor likes “Outcasts” very much:

“The past couple of years have seen a surge in antipathy toward women in science fiction and fantasy, a sort of infantile but brutal reactionary tantrum from male fans of genre work.

Bristling at greater representation of women in the art form and its fandom, these sad fools have begun to feed into the general movement of men’s rights activists (MRAs) who, like people slapping #alllivesmatter hashtags left and right, have completely missed the point.

It’s a delightful irony, then, that this summer marks the 200th anniversary of the invention of science fiction … by an 18-year-old woman. As MRAs rage about the violation of the saint of their nerdy childhood — “Ghostbusters” — I celebrated the genesis of the genre by reading a fantastic book about the three fateful days leading up to that creative epiphany: The invention of Dr. Victor Frankenstein and his terrifying yet heart-breaking monster by Mary Shelley.

When her mother — feminist philosopher and writer Mary Wollstonecraft — died a month after her birth, Mary was raised by her politically radical father. Inspired by the looming shadow of her mother’s notoriety and her father’s ideals, she became a brilliant free-thinker herself. At the age of 17 she married poet and philosopher Percy Shelley, recently divorced, despite a very public outcry in early 19th-century England.

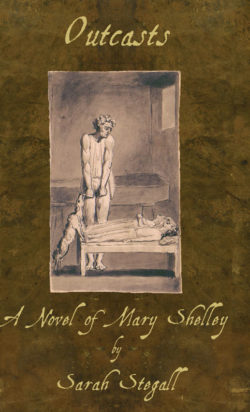

In “Outcasts: A Novel of Mary Shelley” (Wings Press), Science fiction author and critic Sarah Stegall — after obviously thorough research — explores three days in June of 1816, when the newly married Shelleys and their infant son William were staying at near Lord Byron’s villa on Lake Geneva with Mary’s half-sister Claire Clairmont.

Using a limited third-person perspective, Stegall explores the intricacies of the relationships among these four and physician John Polidori, building to what has been widely called “the most famous literary party in history” — the night that Lord Byron challenged his friends to write ghost stories.

At the heart of this novel lie the conflicting pressures on the five lives: Lord Byron, for example, makes a great show of being a profligate free-thinker, but he is caught in the web of aristocratic privilege and expectations that he cannot escape. His lover Claire relishes their collective thumbing of noses at traditional society, but she also wants Byron to give their relationship an imprimatur of respectable exclusivity.

Mary and Percy Shelley are struggling with her father’s reaction to their relationship, and one of the most moving elements of the novel is Mary’s attempt to reconnect with William Goodwin despite his disappointment in his daughter. Their conflict feels a precursor to the literary dysfunction of Victor Frankenstein and his monster.

But not all is soap opera. Much of the three days is spent in compelling philosophical conversation that steadily lays the groundwork for Mary Shelley’s fateful nightmare vision. The friends debate human nature and the soul, women’s rights and galvanism, ghosts and other eldritch beings.

When in fitful dreams Mary finally sees the “pale student of unhallowed arts” kneeling beside the abomination he has created and then wakens to take up her pen and tell their tale, the reader has become so wholly invested in this crux of literary history that goosebumps stand out on the arms and they immediately seek out that battered copy of “Frankenstein.”

Stegall’s writing is so perfectly evocative of those times, so emotionally powerful, that segue into the incomparable science fiction classic feels utterly seamless.”

David Bowles is an author, critic and translator. You can contact him at www.davidbowles.us.