Once again, The Infinite Bard is showcasing some of my fiction. This is absolutely free! Please visit their website to leave comments and enjoy much more free fiction.

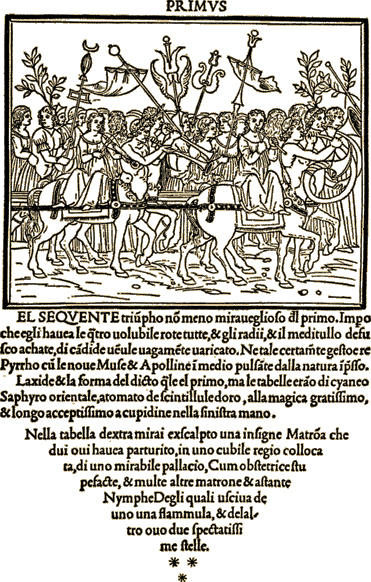

This story is dear to my heart, dealing as it does with the history of the printed book. Aldus Manutius essentially invented the book as we know it today, right down to inventing the typefaces we know and love. But did one of his most intriguing texts once belong to the notorious Lucrezia Borgia herself?

Authenticity

“You’re late,” the skinny clerk hissed at Claudia as he opened the creaking wooden door. “The meeting has already begun.”

Claudia Rossi assumed as dignified a look as she could. She knew it wouldn’t be that effective, given her round, pudgy face, but she refused to be intimidated by Jacopo. “Please take me to the Director.”

The black-clad clerk closed the door and gestured for her to follow him. He led her up the long, crumbling stairs to the Palazzo’s second story. The Fondazione Antico Libro, the Foundation for Antique Books, was housed in a Venetian palace as old as the practice of printing itself, here on one of Venice’s 118 tiny islands. As they passed a window in the stairwell, Claudia caught a whiff of Venetian summer: canal water, sunscreen from a million tourists, cooking oil, garbage, and of course the constant, underlying tang of mildew. Claudia adjusted her hold on the slim portfolio under one arm, and watched her feet on the slippery stairs.

The clerk led her down a dimly lit hallway, and opened a black-painted door. “La Dottoressa Rossi è arrivata,” he said loudly. “Doctor Rossi has arrived.”

Claudia paused on the threshold, getting her bearings. Wooden tables bearing carefully arranged manuscripts and books filled the high-ceilinged room. The smell of old paper, dried leather, and ancient glue brought memories of a dozen libraries to her. At the other side of the room, four men turned to look at her; she felt a flush rise along her cheeks.

“Mi scusi, signori,” she said. “Excuse me, gentlemen.” She cleared her throat. “The vaporetto brought me to the wrong address at first.”

A tall man in a beautifully cut grey suit rose and executed a half-bow. “I am sorry that you were inconvenienced, Doctor,” he said. His voice was as silky as his suit. He held a chair for her. “The water taxis are always erratic at the height of tourist season, but it is delightful to see you again. Will you not be seated?”

Feeling nervous in front of all these eyes, she tucked the skirt of her navy blue suit under her as she sat.

“You have met everyone here?” the tall man said. Without waiting for her to answer, he swept a hand along the row of folding chairs ranged in front of a long wooden table. “I am sure you know Professor Bruno Piriano, of the University of Bologna.” A short, pudgy man with a halo of white hair and a tan linen suit bowed to her from his seat, smiling vaguely.

“And Signore Giovanni Moretti, of the faculty of arts of the University of Florence.” An elderly man wearing a wrinkled blazer blinked at her. “Pleased to meet you,” he said in a deep voice.

“And of course, you know our Director, Doctor Paolo Agnelli, head of the Fondazione.”

He nodded at the man seated behind the table, whose slick black hair looked a decade younger than his sagging face. The Director shuffled a few papers. “Thank you, Mario,” he said. He glanced at Claudia out of sharp black eyes. “I take it you have met Signore Castello before?”

“Of course,” the tall man said before she could reply. “We met in Geneva, at a reception given by my employer. I was quite impressed with her education and address. When my employer decided to sell his copy of the Gli Asolani to the Fondazione, I naturally thought of her.” He smiled charmingly at Claudia. “My employer desired her opinion in this matter, as well.”

The Director did not look pleased. “You understand, Signor Castelli, that the authentication of so rare a volume is a most serious matter, requiring the highest expertise. We usually require the opinions of, forgive me, Signora, more mature examiners.”

He gestured at the table, where two books lay open, side by side. Both of them had the ivory patina of age, the pages lying open and densely packed with black, closely spaced printing. Knowing what one of them was, Claudia found that she was holding her breath.

Castelli leaned forward in his chair. “Nonetheless, my employer insists on Signora Rossi’s presence. There is, I believe, some family connection.”

“A remote one,” Claudia murmured, embarrassed. “If I may, Director? My credentials.” She reached into her briefcase, but the Director shook his head.

“Since Professor Opizzi has fallen ill, and we are short of time, your credentials must be accepted.” He tapped a finger restlessly on the table in front of him, between the two open books. “I know that you are new to the field, Signora Rossi, but I assume you know that we restrict our authentication to four criteria?”

“Paper, provenance, ink and typography,” she said in a low voice.

“Excellent! We have already heard the provenance report from Professor Moretti,” the Director said, fixing him with a hawklike stare. “But perhaps he would care to repeat his conclusions? Just the finale, please, not the supporting detail.”

Moretti rose to his feet, puffing slightly. His face was round and red. He smiled at Claudia, but addressed the group. “The book Signore Castelli’s client wishes to sell to the Fondazione is claimed to be a rare first edition of Pietro Bembo’s poetical work, Gli Asolani.” He folded his hands together, and addressed a distant corner of the room. “This work is known to have been printed by Bembo’s friend, Aldo Manuzio, also called Aldus Manutius, of Venice. Aldus was the first printer to set up a press in the city of Venice, in 1495 —”

“Mi scusi,” the Director interrupted. “I maintain that the first folio of the Organon was actually printed in 1494, making it a year earlier —”

Moretti waved away the objection. “Irrelevant, Director. What matters at this point is that this particular edition is claimed to be Bembo’s gift to his mistress, Lucrezia Borgia.” He took white cotton gloves from his jacket pocket and pulled them on. Approaching one of the open, faded books, he turned a page carefully. “As you can see, on the title page we have a very faint signature, ‘Lucretia de Borgia’, and the handwritten date, 1503.” He turned another page reverently. “Here, on the flyleaf, a hand-drawn sketch in pencil, with the initials LDB below it. If authentic, this would be the only known portrait of Lucrezia Borgia.” He opened a folder, took from it a single photograph, and laid it on the table.

A discreet chime sounded. With an apologetic smile, Castelli pulled his cell phone from a pocket and turned away, murmuring.

Moretti looked annoyed, but continued. “I have here a copy of the will made by Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, the third son of Lucrezia Borgia —”

“Her fourth son, if we count—”

Moretti glowered at the Director. “If you please.” The Director raised an eyebrow but subsided, and the little professor continued. “The third son of Lucrezia Borgia, Ippolito, whom she bore to her husband, the Duke of Ferrara. Like his mother, Ippolito was a noted patron of the arts; many of his letters and books are housed in the archives of the family seat in Modena. Among the items inventoried at the time of his death are a book titled Gli Asolani, listed as belonging to ‘la duchesse’. This duchess was his mother, Lucrezia Borgia, who was known to have had a passionate affair with Pietro Bembo, the author of Gli Asolani. I consider the provenance to be established, and will testify to that.” He sat down abruptly and drank water.

Castelli put away his cell phone and turned back to the group.

Bruno Piriano rose to his feet. “I will now address the issue of the paper,” he announced loudly. He took a handkerchief from an inner pocket, and delicately patted his mouth. “My examination of the paper on which this book is printed was conclusive. Analysis shows that it is of the correct weight, age and composition. Chemical and stereoscopic analysis of a sample pulled from the counter-leaf shows it to be composed primarily of cotton rag, whose botanical and chemical signature place it in Italy in the early sixteenth century.” Piriano bowed to Castelli. “I am willing to swear that this paper was manufactured in Italy sometime in the latter part of the 1400s, or the early part of the 1500s, no later than 1510.” Piriano sat down.

“As the representative of the book’s owner, I will be delighted to bring him this decisive proof as to its authenticity.” Castelli said in his deep voice. “Perhaps we can now enter into negotiations —”

“Not quite so fast, if you please.” The Director held up a hand. “I have here your decisive proof. I regret that it does not support your employer’s claim.”

“I am sorry to hear it,” Castelli said coolly. “Please explain.”

The Director rose to his feet and looked down his nose. “You know, of course, that Aldus Manutius invented the printed book as we know it today. His typefaces were hand carved in lead by Aldus’ cutter, Francesco Griffo, in 1495. His work is distinctive and unique.”

He let his hand hover over the other book lying open on the table. “Here, we have a copy of Dante’s Inferno, printed in 1502 by Aldus Manutius himself, with corrections in his own hand. I personally acquired and authenticated this edition myself, twenty years ago. It is the accepted reference against which we judge new discoveries.”

“The gold standard,” murmured Piriano. Moretti nodded his agreement.

The Director opened a file folder, extracted some papers, and passed them around. “Here is a magnified copy of the title page of Signor Castelli’s book. Here is also a randomly selected page, and the colophon. All are in the same typeface as our ‘gold standard’. Please note the areas I have marked; the worn ‘t’, the slightly bent ‘i’, and the missing middle portion of the lowercase ‘s’. These are characteristic of normal wear and tear on a lead typeface of the early 16th century.”

Castelli shrugged. Claudia caught a whiff of expensive cologne. “Then the book was printed in 1503, as it says in the inscription.”

The Director shook his head. “It is not that simple. Consider two books: one printed from the newly carved type, another printed ten years later. In the years intervening, hundreds, if not thousands of books have been printed using those same letters. Lead type wears down over time. It is easy to compare newer and older editions from the same press, and see how the letters deteriorate with use.”

Castelli rubbed his chin. “Yes, I begin to understand. The earlier and later books form the end points of a timeline, with my client’s book in the middle. So you believe all three books were printed from the same type, and therefore will show a clear progression of wear? Then my client’s book was printed in 1503, a year after your ‘gold standard’, the Inferno.”

“Not precisely.” The Director, who had looked pleased at Castelli’s quick grasp of so complex a concept, now frowned. “I fear that my examination does not bear out that sequence.”

“Pardon?” Castelli’s voice was ice cold.

“I am afraid that the type on your client’s book appears to be less blurred than on the Dante.”

Claudia felt tension in the room.

Castelli said, “I am not sure what you mean. How can the ‘gold standard’ have type more deteriorated than a book printed later?”

“It can’t,” Moretti cut in, his voice harsh. “Which means that your client’s book is a fraud.”

“Fraud?”

“Or shall we say, a mistake,” the Director said. “I do not say your employer is attempting to deceive anyone —”

Moretti snorted derisively.

“—But I do think he may have been, himself, deceived.”

“But the provenance, the paper, they contradict you,” Castelli said.

“The provenance can be misleading. And it is possible, using very sophisticated modern methods, to erase the print from an old book, thus producing authentic ‘old’ paper.” The Director waved a hand. “But the progression of wear in type is unmistakable, Signore Castelli. It is definitive. There can be no doubt. I have only convened this meeting out of respect for your client.”

The Director picked up the contested volume, carefully closed it, and handed it across the table to Castelli. “Please thank your client for his diligence and integrity in bringing this work to be authenticated. But I am afraid the Fondazione cannot purchase it for our collection. The Fondazione, out of respect for your employer, is willing to buy it as a curiosity, no more. Certainly not at the price your employer suggested.” His tone brooked no dissent.

Castelli made no move to take the book. “This judgement seems a little hasty to me. Two of your examiners support my client’s claim.”

The Director shrugged, and continued to hold out the book. “I know your employer will be disappointed, but alas.” He shrugged eloquently. “Such is the nature of antiquities.”

Claudia rose to her feet. All eyes turned to her; the Director glared in surprise. “I have not yet offered the results of my examination,” she said. She heard the tremor in her voice and swallowed. “Perhaps you should withhold your final assessment until Signore Castelli and these other gentlemen have heard it.”

The Director dropped the book with a thud to the table. “Signora Rossi, surely this is unnecessary.”

“Perhaps you think our work is sloppy,” Moretti growled at her.

“Not at all,” Claudia said. Her hands felt clammy. Only six months ago, she had been defending her doctoral dissertation in front of a group of experts very much like this one; she found herself flashing back to that anxious afternoon. “I … have other evidence, of a different nature.”

“I do not wish to embarrass Signore Castelli with further proof of forgery,” Director Agnelli said. “Please, let us adjourn and end this gracefully. We have arranged for wine —”

“I would like to hear what she has to say,” Castelli said forcefully. He smiled at her. “She has come so far. From California, am I correct?”

Claudia nodded. “From UCLA,” she said.

“Then it would be discourteous not to hear her out,” Castelli said. He gestured for her to continue, and the others settled back in their chairs. Claudia was left standing, acutely aware of her youth, of being the only woman in the room, of her relative inexperience compared to these men of international reputation and scholarship. She swallowed, and opened her portfolio.

“My area of investigation is ancient inks and pigments.” She passed around neat printouts, with graphs in color. “Materials used during the Renaissance were made from local sources. After decades of X-ray and chemical analysis, our databases in Los Angeles, as well as those of the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Paris-Sorbonne research unit in art history, are comprehensive. They contain samples and profiles of minerals, materials, and formulas used to make ink from the days of ancient Egypt up to the present.”

The Italian professors turned the printouts this way and that. Moretti leaned over and whispered to Piriano, glancing at her.

“As you will see, I analyzed ten samples of ink used in the production of manuscripts from the period,” Claudia said. “All were examples of oak gall ink, also known as iron gall ink.” She glanced at the men. “Of course you are all familiar with iron gall ink?”

Piriano blinked slowly. “The ink used for thousands of years in Europe, distilled from the galls of the gall wasp, found on oak trees.”

Claudia nodded. “The tannin in the oak galls was necessary to make the ink bite into the paper.”

“And Aldus, like all other printers for hundreds of years, made his own ink. We understand,” said Moretti. “Get on with it. I have another meeting this afternoon.”

Claudia stood straight. “Oak gall ink, being made of an organic substance, is amenable to genetic testing. Here, we see the DNA profile of Signore Castelli’s client’s book—the ink is unmistakably the product of Quercus frainetto, also known as the Italian oak. It is native to southeastern Europe and was commonly found in the northern Mediterranean, specifically in the countryside around Venice.”

Piriano shrugged. “So?”

She pushed another paper forward with one finger, watching the faces of the men. “This is another DNA analysis. It shows, clearly and conclusively, that the ink was manufactured from the galls of Quercus virginiana, also known as the Southern live oak.”

A pause, and then Piriano glanced up sharply. “Virginiana?”

Moretti scowled at Claudia. “I do not understand. Isn’t Virginia in America?”

“It is,” said Claudia firmly. “And the Southern live oak was unknown in Europe in the 16th century. In fact, it was not known until the English colonized Jamestown in 1607, over one hundred years after the Gli Asolani was printed.”

A hush fell on the room; a breeze from the window brought the faint sounds of tourists passing below. Castelli frowned. “You believe my client’s book was printed using American ink?”

Claudia shook her head. “Not your client’s book, Signore.” She turned and placed her hand on the other book on the table. “The sample came from this book.”

“The Inferno?” Moretti said. “Impossible! It was printed in Venice! The Director verified it himself!”

“This is absurd,” the Director said, rising to his feet. “What game is this, Signora Rossi? You have made some clumsy mistake.”

Claudia stood firm, looking from one man to another. “I ran the analysis four times, then had my colleagues at the UCLA lab run it twice. The results were the same each time.”

“Atroce! Scandaloso!” cried Piriano. “You realize what you are saying? That the gold standard itself is a fraud?”

The Director shook his head. “Let us not terrorize the poor girl,” he said. “She is young, she is enthusiastic. She has made a mistake. Signora Rossi, how could you even have obtained a sample from this book?” He picked up the Inferno in one hand. “It is always locked away.”

Castelli rose to his feet, and his movement was so deliberate and controlled that it held the attention of all in the room. “I gave her the sample, three weeks ago,” he said quietly.

Piriano and Moretti looked shocked; the Director’s face grew white. “How did you-” He glanced down at the book in his hand, and with his other hand turned over a few pages. He stopped, frozen.

Piriano leaned over to look. “Infame! Someone has defaced this book!” He grabbed it from the Director’s hand and held it out. At the corner of a page, a one inch square had been cut out. “How could you destroy such a treasure!”

“Because it is no treasure,” Castelli said. The room fell silent except for the cries of the vendors, the roar of the vaporetti outside in the canal. “Your ‘gold standard’ is a fake.” His eyes met the Director’s. “As is your leader.”

Piriano and Moretti stared at the Director. “Che cos’è questo?” Moretti demanded. “What is he saying?”

Castelli stepped forward and took the Inferno from Piriano’s hand. “I am saying that for twenty years, you have been deceived by this man, who has used his forgery of a famous book to enrich himself through fees and bribes. And, finally, to gain the Directorship of this institution.” Castelli reached into his breast pocket and took out a slim case. He turned it to show his identification; the globe and sword of the International Criminal Police Organization drew the attention of both men.

Piriano gasped. “Interpol?”

“This is an outrage,” the Director said. All eyes on the room moved to him. “Some enemy has devised this. I will not be party to it.” He reached for the book, but Castelli held it out of the Director’s reach.

“This is evidence,” he said. “It will be presented at your trial.”

“Trial?” Piriano’s voice climbed an octave. “You are arresting him?”

Castelli’s eyes did not leave the Director’s. “I cannot. It is not within my power.”

“Exactly.” The Director’s eyes were cold, but his voice shook just a little. “You have no power, no authority. You are nothing here. You, signore, are the fraud.” He strode towards the door.

Claudia looked up at Castelli, who merely turned to watch. “Aren’t you going to stop him?”

The Director stopped with his hand on the door. “Your superiors will hear of this,” he hissed. Then he opened the door and went through.

“But he’s getting away!” Moretti said. Piriano slumped into his chair and held his head in both hands.

“Never fear,” Castelli said. He slipped his card case back into his breast pocket. “There are two agents of the Polizia di Stato waiting at the bottom of the stairs. And they most certainly do have the power to arrest him.”

Piriano let out a moan. “Do you have any idea what this means? Twenty years that man has been verifying artifacts, a trusted authority in the field. I myself voted for him when he was made Director five years ago. His entire reputation, the reputations of others, rest on that book.” He looked up at Castelli. “Surely there is some mistake?” he said pleadingly.

Castelli said gently, “I am so sorry, Signore. But there is no mistake. We have suspected him for some time.”

Moretti glared at Claudia. “And you? Where do you come into this?”

From downstairs, a sudden outcry, then pounding feet, more yelling. “Ah. I am afraid Director Agnelli has run into the polizia,” said Castelli. “As for Signora Rossi, I approached her for help when a German collector began to doubt the legitimacy of a book that the Director had ‘authenticated’.” He turned and bowed to Claudia. “The Signora has been most helpful in my investigation. Mille grazie!”

“How could this have happened?” moaned Moretti.

“Simple enough,” said Claudia. “Assuming he had access to a cache of old paper and old leather, he could reproduce a book from the 1500s. He just now explained how he did it—”

“How arrogant,” Castelli said, shaking his head.

“—By erasing the print from an old book of the right age, re-printing it, and binding it again.”

“Where would he find the type to print it?” cried Piriano.

“That, and not the book, was his great discovery,” Castelli said calmly. “Agents of the state police have already executed a warrant and searched the Director’s private residence. That was the phone call I took during our meeting. They have found a complete set of type, hidden under the floorboards of his study. We have in custody the plumber who found it in the foundations of an old Palazzo and sold it to Agnelli twenty years ago.”

“He realized that he could not make a name and reputation from a set of old type,” said Claudia, repacking her portfolio. “But he knew that he could make a book from the old type. And that would make him famous, respected and powerful.”

Moretti squinted. “If this is so, if he had the ancient book and the old type, then the only thing the Director could not have copied —”

“Was the ink,” said Claudia. “Raw ink could not have survived the centuries; it would have hardened, or rotted away entirely. Even if he had found an old printer’s cache, the ink would have been unusable. So he had to make his own.”

“But this is Venice,” said Moretti. “Would he not have used the very same oak trees from these very same hills that Manutius used?”

Claudia smiled. “Unfortunately for him, most of the few remaining native oaks on the mainland are under strict control of the Conservation Service. He would not have had access to the galls he needed, so he used Virginia oak galls, which he could have found anywhere in modern Italy.” She shook her head. “He never expected to have his work questioned, not after twenty years.”

Moretti groaned. “Twenty years! Twenty years of lies! The Dante is counterfeit!”

“Dante, indeed,” muttered Piriano. He glanced up to meet the puzzled looks of the others. “In the Inferno, the eighth circle is reserved for frauds, forgers and thieves. For someone to have deceived us so long, so completely…” He raised his hands in a helpless gesture. “Agnelli deserves to spend eternity in the eighth circle.”

“Come, Bruno,” Moretti said. “I need a drink. You do, too. Then we have many, many phone calls to make.” He helped the other man to his feet, and they slowly walked out.

“This is a terrible blow to the Fondazione,” Claudia said.

“Not necessarily,” Castelli said. “Consider it like a house cleaning. Now that the dirt has been exposed, it can be swept away and trust restored.”

She looked at the book in Castelli’s hand. “So, the Gli Asolani is genuine? That really is Lucrezia Borgia’s portrait?”

Castelli nodded. “Most likely. Her lover didn’t write a dedication, he drew her picture in the book instead. She would have treasured it.” He looked around the room. “They wrote so many letters. Beautiful letters. Lord Byron saw them, when he lived here. He called them the most beautiful letters in the world.” He looked back at the book in his hand. “But Pietro only drew one picture of the woman he loved. This one.”

Claudia opened the book to the sketch. “In one of his poems, Bembo said, ‘you, like Narcissus, feed yourselves on vain desire and never understand that they are merely shadows of true beauty’. He had true beauty before him.”

“And the Director knows only vain desire. He cared nothing for the antiquity, only for reputation.”

“He will have a different reputation now,” she said.

He took her arm and turned her towards the door. “So will you, Signora. May I ask, have you considered a career in law enforcement? In, perhaps, the apprehension of art forgeries? Let us have dinner, and discuss your future.”

Claudia smiled, and he opened the door, and they went out of the quiet wood paneled room into the bustle of Venice.

THE END